Skeuomorphism and Flat Design

within Contemporary Design Movements.

‘Designers

loaded everything with drop shadows and gradients to give the illusion of

depth, and of a light shining above and to the side. They did this because it

was comfortable. Society had to adapt to perceiving things on a digital

screen.’ (Greenstein, A, 2013)

‘Skeuomorphism’

and ‘Flat Design’ are two terms that refer to different design movements that

are at the opposite ends of the spectrum in regards to aesthetics,

functionality and usability. A

skeuomorphic design emulates objects in the physical world to make it easier

for people to feel more familiar with a device. Flat design does the opposite, it doesn’t

employ any three dimensional realism by disregarding gradients, bevels, shadows

and lighting, instead favouring typography and blocks of colour. With such high

contrast in philosophy, flat design offers an alternative to the familiarity of

skeuomorphic design. In his essay ‘laptop aesthetics’, Adrian Shaughnessy

suggests, ‘Within the digital domain, for so long the place for graphic

innovation, there are signs that a burgeoning aesthetic maturity has arrived

offering an alternative to Toy Story 3D-ness.’ (2003)

This essay attempts to

discuss what exactly flat design and skeuomorphism are, the pros and cons of

both and the possibility of a new and more balanced system that combines

successful elements of the two.

‘More than ever,

technology constraints have disappeared, and designers have their version of

the mythical perpetual motion machine — a new medium where pixels are

infinitely available and infinitely malleable. We should focus on setting them

free.’ (Maeda, J, 2013)

Before

writing about Skeuomorphism it is necessary to define what it means. The word ‘Skeuomorph’

originated from Greece and is compounded from the Greek words skeuos, container

or tool, and morph, meaning shape. The Oxford Dictionary defines the word as

‘an object or feature, which imitates the design of a similar artefact made

from another material.’ Around 1980 the term was applied to material objects

but now it is most commonly associated with computer applications as well as

mobile interfaces. Skeuomorphs are designed to familiarise the user by creating

a connection with past experiences that are ingrained into society, making new

mediums feel more comfortable and easy to understand.

‘At its core, skeuomorphism is more than just the

gratuitous mimicry of the look of a leather calendar. Buttons, shadows, ridges

and toggles are skeuomorphic functionalities. Swiping, pushing and pulling are

also real life interactions and could perhaps be called skeuomorphic, since

they are not absolutely necessary to the functionality of the interface. But

this is where the lines blur and I would argue that although not necessary.

They make it easier for our 3D brains to understand how to interact with a 2D

interface and thus serve an important purpose.’ (Sanchez, E, 2012)

Donald

Norman highlights this notion in his book ‘The Psychology of Everyday Things’ suggesting,

‘the human mind is exquisitely tailored

to make sense of the world. Give it the slightest clue and off it goes, providing

explanation, rationalization, understanding.’ (1988, p2) Victor Dewsbery takes

this point about skeuomorphic design further in relation to technology and

computer interfaces describing a need in digital design for a metaphor that ‘is

often used to place the individual program routines into a meaningful context

that can be understood by the user.’ (2002, p112) Kuang would argue ‘When you’re looking at

computer windows that layer on top of each other like paper, you’re looking at

metaphorical rules for how computer interactions should behave, drawn from the

physical world.’ (2013)

Therefore, these ideas

about what Skeuomorphic design is comprised of have common threads that exist

in all the definitions proposed here. Skeuomorphism could be considered to be the

manifestation of ‘root metaphors’ that are now embedded in all of our day-to-day

interactions with objects and products. This gives users that sense of a

‘connection to past experiences’ and a familiarity that is sometimes necessary

for people to engage with products, emerging technologies and the design of

digital interfaces.

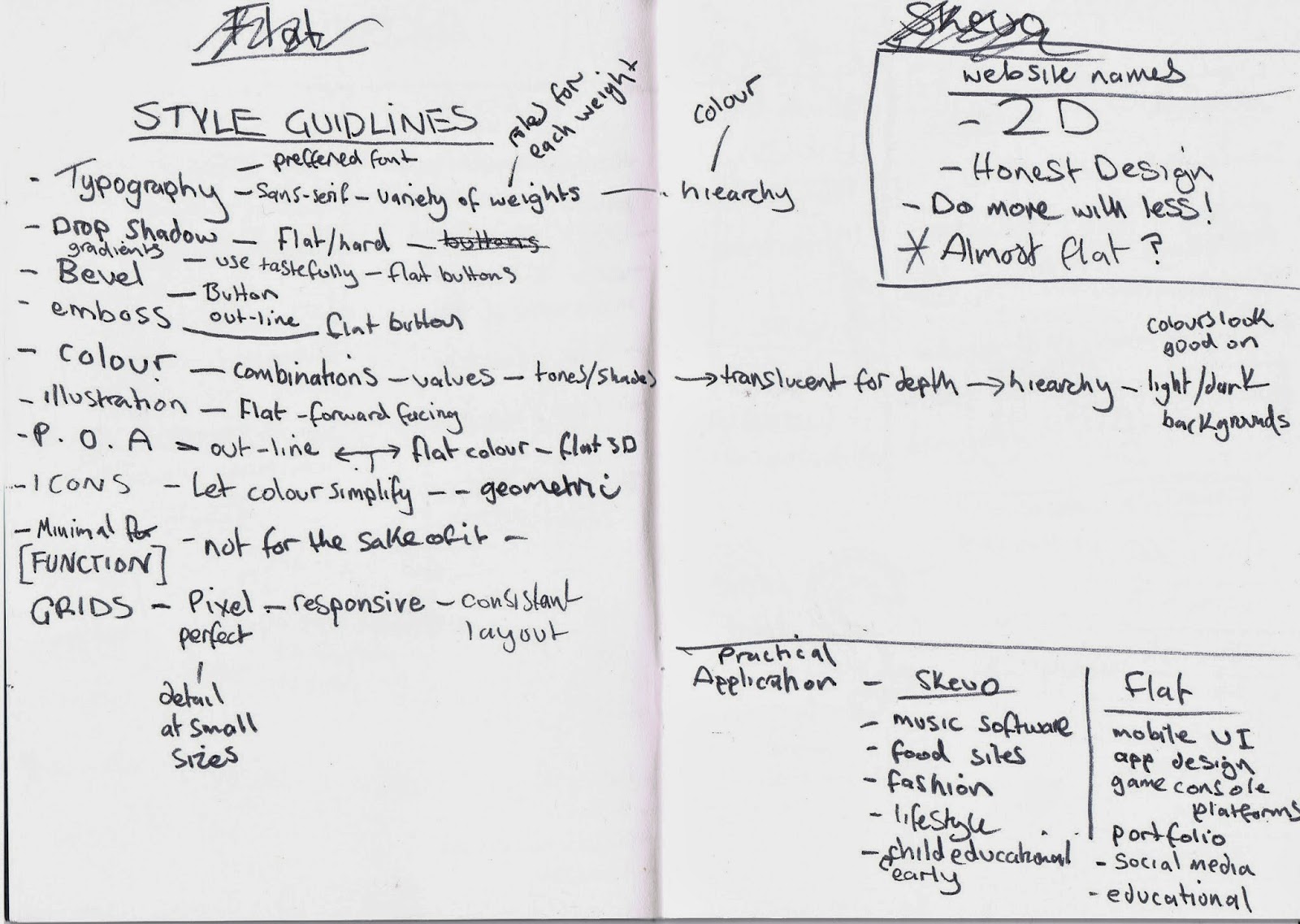

The term ‘flat design’ refers

to a design trend currently influencing the digital domain that has grown in

popularity over the last two years. It disregards visual clutter such as drop

shadows, gradients and lighting effects, instead favoring vivid colours, simple

shapes and crisp typography.

‘As each new technology matures, customers are no

longer happy with the flashy promises of the technology but instead demand

understandable and workable design.’ (Norman, D, 1988, p15)

The trend may be current,

however the philosophy is not. The aesthetics and ideology associated with flat

design can be clearly seen in a historical context when compared with modernism,

a philosophy from the 1920’s that emphasized simplicity, truth to materials,

the progression of technology and the well-known phrase ‘form follows function.’

Massimo Vignelli confirms this in

his essay ‘Long Live Modernism’, stating ‘modernism was and still is the search

for truth, the search for integrity, the search for cultural stimulation and

enrichment of the mind. Modernism was never a style, but an attitude,’ (1991) a

sentiment and ideology that can be clearly seen in today’s current flock of

technology, mobile and web applications. Microsoft’s ‘Windows 8’ or Apple’s

‘Maverick’s’ user interface are excellent examples of how when ‘flat design’ is

applied correctly, it can exploit the virtues of designing for the screens two

dimensional space, adding only what is necessary to maximize usability and

functionality. Stefan Mumaw describes this concept stating that ‘designers

also use visual tools-colour, shape, size, and layout-to communicate order,

emotion, mood, and attraction. These elements allow designers to design and

create simple structures from complex assets. In short, designers can make a

lot look like a little. They do that by applying not only what they know but

what they have experienced. Simplicity is rarely the result of too little to

say, but rather, how it is said.’ (2002, p65)

Certain

aspects of graphically intense design styles are considered bloated and

unnecessary by ‘flat design’ advocates, as is the use of effects such as drop

shadows or textures. In his writing ‘Material Honesty on the Web’, Kevin

Goldman suggests ‘without all the shading, shadows, and bulbous buttons, we get

a flatter (or honest, or native, or authentically digital)

web. Call it what you will, the flat web focuses more on content.’ (2013) This

‘visual clutter’ is replaced with simple 2 dimensional objects, typographical

styles and block colours that create a relationship between the figure and

ground. In turn, this establishes a visual hierarchy in which the content is

placed with more importance than other visual elements. ‘The palette

of emotional design for flatlanders is instead temporal. Temporal beauty lives

in state-change animations, nuanced timing effects, strategically placed user

feedback, and other “interesting moments,” not drop

shadows and Photoshop layer effects. Flatlanders build all kinds of emotion and

depth combining these moments with delightful microcopy, personality, and typography. All honest—all

web—all good.’ (Goldman, 2013)

This idea is fundamental to the

recent success of flat design in the digital space due to technological

advances in screen display sizes and monitor resolutions, the mobile web and

user interfaces.

In order to illustrate

the ideas talked about above it is necessary to analyze examples of

skeuomorphic and flat design. This will form the basis for a discussion of the

benefits and draw backs of the two. The skeuomorphic image refers to the Apple

Mac operating system 10.1 and the flat design image references the Windows 8

operating system.

In regards to ‘visual

clutter’, figure1 overloads the page with information; the main points of

interaction are displayed at the top and bottom of the page with the content in

the middle. The layering of documents mimics the conventional method of

workflow by imitating a physical desktop space with documents placed on top of

each other. This is an example of skeuomorphism transferring restrictions of

the physical into a digital space. In

his writing ‘Flat Design vs. Skeuomorphism - why you are comparing oranges to

apples’, James Duval comments on a

similar issue with skeuomorphic boundaries. ‘Realism can bring the limitations

of the real world with it in its digital form. Think of how most calendars

still show you days on a monthly basis, or calculator apps only show you one

line for the results, rather than allowing you to keep track of your history or

multiple calculations at once.’ (2013) In figure2, it’s clear to

see that a strict grid system has been put in place. This creates a consistent

layout that helps to organize applications, giving structure and clarity to

information. Garaza would argue that ‘society is quickly moving into the

Jetsons era and the future is now. This means that some of the original design

patterns that we leveraged to introduce people to new technologies are also

changing. As users get more sophisticated, design systems evolve into something

that is more suitable to the medium, rather than emulating models from the

past.’ (2013) This is a good example of how form can follow function as the

content avoids unnecessary noise allowing it to become the main focal point.

In figure1, the user

interface relies heavily on skeuomorphic indicators to inform the user of

points of interaction. For example, the software icons in the dock at the

bottom of the page use techniques such as gradients and lighting to portray

depth, which in turn creates hierarchy and helps separate the information from

the background. In figure2, the majority of icons have been stripped of

decoration, solely relying on colour and type to decipher information; this

could be a problem for some users that are unfamiliar with navigation. Norman

comments on this by suggesting, ‘there must be some way of knowing what action

and where it is to be done. This requires a

convention of highlighting, or

outlining, or depiction of a actionable object.’ (2004) This is supported by Nishant Agrawal as he

suggests, ‘Gradually, you start

understanding, and appreciating, the detail of skeuomorphism. There are many

layers which separate the button from the background – shadow, color, gradient,

border … You start to understand that each has a role to play and together they

give a unique individuality to the button.’ (2013) However this could be argued

to be something of a one-dimensional outlook on the progression of digital

design, stalling innovation and creativity. In his article ‘The Real Problem With Apple: Skeuomorphism In iOS’,

Tim Worstall suggests ‘that may well

have made sense twenty years ago, when most in the world of work were familiar

with the physical world example. It’s quite possibly less so now when a goodly

chunk of the labour force have never even seen one. And the perpetuation of

this organisational form might be limiting innovation in more modern ones.’

(2012)

As discussed briefly in

the last paragraph, a big uncertainty surrounding flat design is the execution

of navigation. Typography and colour have a leading role in successfully

achieving the distinction of points of action. Figure2 is a good example of

this concern; the blocks of vivid colours separate the content from the

background, resembling a panel or button. In his article ‘Flat design, iOS7,

Skeuomorphism and All That’, Turnbull comments on the importance of selecting

an appropriate colour scheme by suggesting, ‘you can still embody flat design

using shades of grey with an accent colour, but adopting new colour trends and

creating a bright, diverse palette can help to create important contrast and

help to recreate effects rivaled only by gradients, shadows and other outgoing

embellishments.’ (2013) Payne challenges this by suggesting good design has ‘to be effective, designers must set

their sights well beyond easy-to-use. We need to convey more than how. We need

to convey what as well. We need to be interpreters, to contextualize and

concisely convey their identity, purpose, and value.’ (2013) Further more, Spiekermann

would argue ‘Cultural parameters like reading habits, literary culture

(or lack of) – our deeply embedded fear of change, all these give an excuse to

imitate the old, even though there are no technical reasons to do so.’ (2012)

This is clearly seen in figure1 where less attention is paid to type aesthetic

and focused more on graphical illustration to communicate a message. Where as

figure2, uses sharp, sans-serif fonts designed to take advantage of higher

screen resolutions, a variety of weights from the same type family have been

carefully selected to enhance an illustration or stand-alone for a call to

action.

Figure1 would

conventionally be classed as skeuomorphic design, where as figure2 can be

classed as flat design. This division between the two can be seen as being

inaccurate because of past connections to certain symbols displayed in figure2.

For example, the icon that resembles a bag is used to communicate the folders

use, to store items. This makes a connection with the users past experience, to

the old and familiar, transferring a message that has been ingrained into

society through the use of metaphors in everyday life. Kuang challenges this

idea of interaction of both design criteria by suggesting, ‘what should the “trash bin” on your computer

desktop look like? After all, it doesn’t really behave like a trash can. Should

it look like a trash can? If not, what could it possibly look like while

still being totally intuitive?’ (2013) Rahul Sen refers to such metaphors as

‘archetypes’. He argues, ‘archetypes can always be deconstructed,

challenged or probed since they merely act as starting points of reference.

There are innumerable examples of archetypes that have been reintroduced to us

in the most puzzling ways in order to question our own understanding of them.’

(2010)

‘In the information-rich

society we will find that users establish many of the criteria for what they

want available and how they want it to be delivered to them. As designers we

must take account of this, and seek to use technologies to satisfy those

desires, as well as to innovate and break through the creative barriers that

will enable us to produce the ‘next big thing,’ (Cook, M, 2001, p364)

To enable the progression of digital design a

compromise could be a possible solution to the problem. For example, the visual

clues of skeuomorphism combined with the functionality of flat design lies

somewhere in the middle, taking successful elements of the two and applying

them in a way that is still familiar and usable. One term used by design

advocates to describe this compromise is ‘skueominimalism.’ Edward Sanchez

describes this idea in his writing ‘Skeuominimalism - The Best of Both Worlds’ as ‘skeuominimalistic design is simplified up to the

point where simplification does not affect usability. And its skeuomorphic affordances are maximized up to the point where it does not

affect the simple beauty of minimalism.’ (2012) Another term used by Mathew

Moore is ‘almost flat design.’ He suggests ‘Almost Flat Design doesn’t ignore the concept of depth. Instead,

depth is used to support comprehension of the interface. But, just like

gradients, this can be done in a subtle way and still allow for separation of

information.’ (2013) Figure3 is the new iTunes platform; this is a good

example of both parameters being used successfully in conjunction. The use of

gradients, shadows and highlights create physical familiarity and are used

subtly and tastefully to indicate points of action without affecting functionality.

Analyzing skeuomorphic design against flat design it

is clear to see the positives and negatives of the two. This suggests the two

philosophies will remain relevant within the digital domain, and by combining

the successful elements from each party, the overall usability and

functionality will be better balanced and appeal to a wider audience. In his

writing ‘iOS 7, Windows 8, and flat

design: In defence of Skeuomorphism’, Grinberg suggests ‘designers

should not simply flatten designs arbitrarily, but also address the functional

qualities of skeuomorphism on each design decision. With these considerations a

balanced approach can drive the optimal design parameters.’ (2013) This is

further supported by Duval as he suggests ‘Flat design isn’t good or bad. It’s just flat. It’s

one company’s solution to the world of responsive design and touch screens but

it isn’t the only solution. You can keep a minimalistic approach while

also using shadows and gradients – as long as you do it tastefully.’ (2013) With

this in mind, the combination of the two design parameters could aid in finding

the solution to resolving the problems of successfully designing for a digital

space.

‘The future is bright for

visual design. Going away are the days of the heavy real-life metaphors of

today’s iOS and as we temper back from the Metro interface, the principles for

highly usable, effective, and efficient design languages are emerging. Let’s

just not forget the lessons of usability we should already know.’ (Moore, M,

2013)

Figure1

Figure2

Figure3

Bibliography

Mumaw, S (2005) Simple:

Websites, America, Rockport Publishers

Dewsbery, V (2002)

Navigation for the Internet and other Digital Media, Switzerland, AVA

Publishing

Norman, D (1988) The psychology of everyday things,

New York, Basic Books

Elsom-Cook, M (2001)

Principles of Interactive Multimedia, England, McGraw-

Hill Publishing Company

Agrawal, N (2013) Why Flat Design Doesn’t Work, While Skeuomorphism

Does:

http://ncrafts.net/blog/2013/06/why-flat-design-doesnt-work-while-skeuomorphism-does/

(Accessed 05.01.2014)

Grinberg,

Y (2013) iOS 7, Windows 8, and flat

design: In defense of Skeuomorphism:

http://venturebeat.com/2013/09/11/ios-7-windows-8-and-flat-design-in-defense-of-skeuomorphism/

(Accessed 03.01.2014)